Crazy People

Opening Reception: 26 April 2012, 6:00 - 9:00 pm

26 April - 17 May 2012

âI live in a world where most of my contemporaries are focused only on things like money, social status, reputation and personal pleasure,â Bui Thanh Tam says of his latest collection of paintings entitled Crazy People exploring the effects of the new hyper-materialism being embraced by many of his compatriots. Tam believes this phenomenon is eroding the countryâs unique culture and values. His âcrazy peopleâ â members of Vietnamâs recently minted class of nouveau riche â grin inanely out of…

âI live in a world where most of my contemporaries are focused only on things like money, social status, reputation and personal pleasure,â Bui Thanh Tam says of his latest collection of paintings entitled Crazy People exploring the effects of the new hyper-materialism being embraced by many of his compatriots. Tam believes this phenomenon is eroding the countryâs unique culture and values. His âcrazy peopleâ â members of Vietnamâs recently minted class of nouveau riche â grin inanely out of…

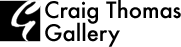

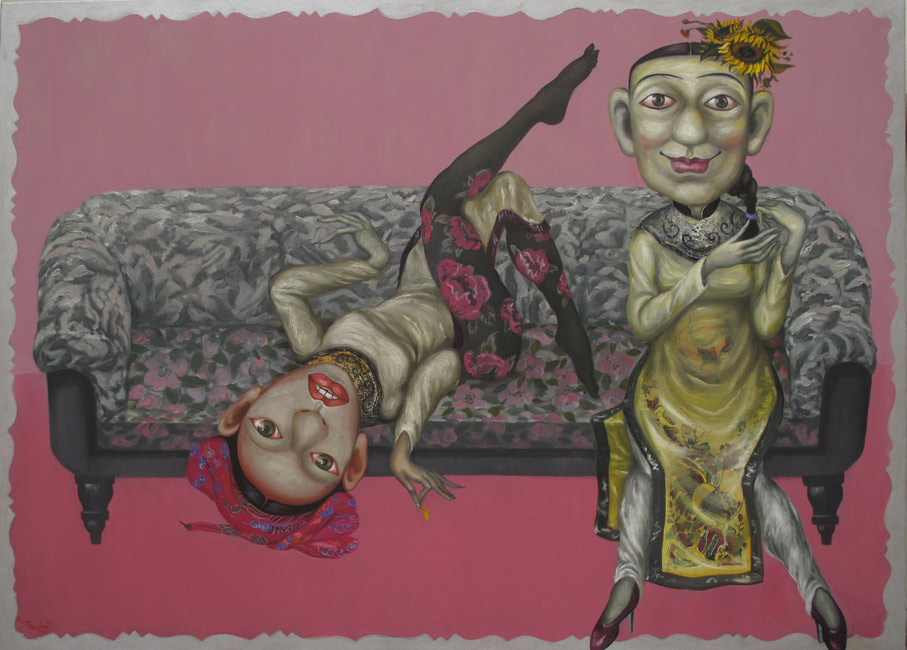

“I live in a world where most of my contemporaries are focused only on things like money, social status, reputation and personal pleasure,” Bui Thanh Tam says of his latest collection of paintings entitled Crazy People exploring the effects of the new hyper-materialism being embraced by many of his compatriots. Tam believes this phenomenon is eroding the country’s unique culture and values. His “crazy people” – members of Vietnam’s recently minted class of nouveau riche – grin inanely out of his canvases as they revel in their privileged lifestyles. For Tam, these fashionable but empty-headed people are slaves to their newly acquired tastes and appetites. In the thrall of Vietnam’s über-capitalist gold rush, they are like puppets manipulated by unseen hands along a luxury-filled, ostentatious, but ultimately meaningless, existence.

While there is an earnest moral lesson at the heart of his work, Tam leavens the potential didacticism through the use of parody and humor. His often whimsical paintings focus on the ridiculous contradictions between his subjects’ contemporary lives and his view of a more traditional Vietnamese existence. Tam gives his characters the familiar stylized faces of Vietnamese water puppets and portrays them with simpleton’s smiles and wide doe-eyed stares. Their silly visages serve as masks behind which they hide their feelings of confusion and inadequacy. Tam’s crazy people are meant to be mocked and pitied but not despised.

Among his inspirations when creating the Crazy People series, Tam cites the Arhant sculptures found in Buddhist temples like the Tay Phuong Pagoda in Vietnam’s Ha Tay Province. According to Mahayana Buddhist tradition, Arhants are at a lower level than bodhisattvas and have reached their liberation from the cycle of life and death known as samsara in an undesirable and self-serving way. Like Arhants, Tam’s crazy people seek their own personal nirvana through a selfish and unworthy path. For them the goal is a life of luxurious decadence and to achieve this they seek to free themselves not from materialism and physical desires, but from the virtues embodied in traditional Vietnamese culture and values.

In the Crazy People paintings, Tam’s characters are dressed in traditional garments and headdresses, a clear reference to Vietnam’s historical and cultural identity. The dresses worn by the women are rendered in bright, lively colors, but at close inspection we find traditionally painted images and representations hiding within them. The figures and scenes are taken from Vietnamese folk paintings and depict historical events, legends and anecdotes that might once have carried meaningful life lessons. Tam is pointing to the confused use of such symbols in modern Vietnamese society where they have become merely ornamental appendages shorn of their original significance and meaning. They are now just so many more pretty things to show off within the glittering lifestyle of the newly prosperous.

Tam uses the well-known image of the To Nu folding screen to emphasize his underlying theme that Vietnamese society is inevitably being coarsened by the loss of its traditional culture. Used especially in Hang Trong and Dong Ho folk paintings, To Nu paintings typically depict demure maidens in a series of panels wearing traditional Vietnamese dress, playing indigenous musical instruments and holding various other iconic cultural objects. In the painting Crazy People VI, a forlorn looking young woman sits holding a violin – the playing of which is an imported fashion in itself – in front of a To Nu screen. Rather than the normal items such as the don nguyet (a traditional Vietnamese plucked, fretted lute with a round body and two strings), a flute or a folding paper fan, the women in these panels flourish knives and swords. There is a price to be paid when people become deracinated, and the transformation of these once charming symbols into smirking, weapon-wielding menaces signifies that cost.

Tam speaks of the influence that the Cynical Realism of Chinese painters has had on his work. Arising in China in the 1990s, the work of the Cynical Realists used humor and irony in confronting their society’s socio-political issues through their art. Featuring characters that often shared the exaggerated grinning face of the artists themselves, the art of the Cynical Realists focused on the transition from the old to the modern that China was experiencing and the confusion arising therefrom. In a similar way, Tam’s paintings can be seen as cynical commentaries on the state of contemporary society in Vietnam. He says they are intended as parodies in that the viewer may find them amusing, but also painful and bitter. Tam’s work could be classed in a new category of contemporary art that might be called “parodic realism.”

Born in 1979 in Thai Binh Province in the northern coastal region of Vietnam, an area known as the homeland of Vietnamese water puppetry, Tam was born post-reunification, but perhaps must be viewed as balancing on the cusp of a true generational demarcation in the country’s history. Unlike Vietnamese born 10 years after him, Tam has clear memories of a time – most notably the period of rationing and scarcity referred to by Vietnamese as “thoi bao cap” – before today’s relative prosperity began its slow and ongoing spread through the country. This was a time before satellite television, expensive brands, and for many, electricity and sufficient food, when the country’s traditional customs and culture were a source of great solace during trying times. Today’s younger generation does not share a living experience of that time, and not surprisingly, they are the segment of the population that has most enthusiastically embraced Western culture.

While Tam’s is an essentially conservative vision, his work should not be viewed as an indictment of Western culture which he calls “civilized, progressive and compelling.” Tam is disturbed by the less positive side-effects of Vietnam’s modernization including the rampant consumerism and narcissism the process has engendered. His ideal result would be a synthesis between the traditional and the modern that would allow the country to flourish and prosper, but would also retain what is unique and special about Vietnam. Tam says, “if we can manage to preserve the roots of our traditional Vietnamese culture as we modernize, in my opinion, the Vietnamese people will be purer and better.”

Bui Thanh Tam currently resides in Hanoi. He is a 2009 graduate of the Vietnam Fine Arts University. Crazy People is Tam’s second solo exhibition in Vietnam and his first in Ho Chi Minh City.

Craig Thomas and Xuan Mai Ardia

Read more

Read less